Objects of entertaining: Introducing the V&A for Paperless Post

Porcelain plates that decorated the dinner tables of 19th-century high society. A teapot that once gleaned like silver—now rich with the patina of time—given as a wedding gift in the 1890s. A beautifully preserved paper menu with lace trim from a banquet nearly 200 years ago.

These are just a few of the millions of fascinating objects that live at the V&A (Victoria and Albert Museum, London). And now, these “objects of entertaining” have found a purpose once again: featuring in our new collection of invitations we’ve made in collaboration with the UK institution.

“ Long a destination for designers and manufacturers, the V&A is an invaluable resource and constant source of inspiration for new creations,” says Amelia Calver, the V&A’s Licensing Research and Development Manager. “With its focus on the applied and decorative arts and design, the V&A not only preserves the past but actively influences design through its collections.”

And influence us, it has. Perusing our collaboration, you’ll find intriguing and artful invitations featuring elements of objects from parties past, designed to inspire and delight guests ahead of your next modern-day event.

Read on to learn more about some of the exquisite objects that inspired our collection, with historical insights from Calver and notes from the designers on our Content Team about how each one was carefully and lovingly translated into a Paperless Post invitation.

“Lace Pattern” by the V&A for Paperless Post

The object: The Lord Mayor’s Banquet Menu – England, 1848

The history: This elegant paper lace menu printed with soft blue ink, from a customary private dinner party at the Lord Mayor of London’s residence in the mid-19th century, features dishes made of turtle and more than 16 dessert options. “This object is part of the V&A’s prints and drawings collection and is one of many examples that showcase the evolution of printmaking,” says Calver. “The collections at South Kensington highlight both historical and contemporary techniques, offering insight into the diverse methods used to create prints over time.”

The design notes: “The delicateness of this paper lace menu meant that it required careful repairs and restoration—digitally, of course—to bring it back to its original glory, says Paperless Post Production Design Manager Kellie Di Chiara. “We also tried to maintain the typographic style of the menu for our invitation with a similar serif font. The striking ship imagery on the menu is showcased in the envelope liner.”

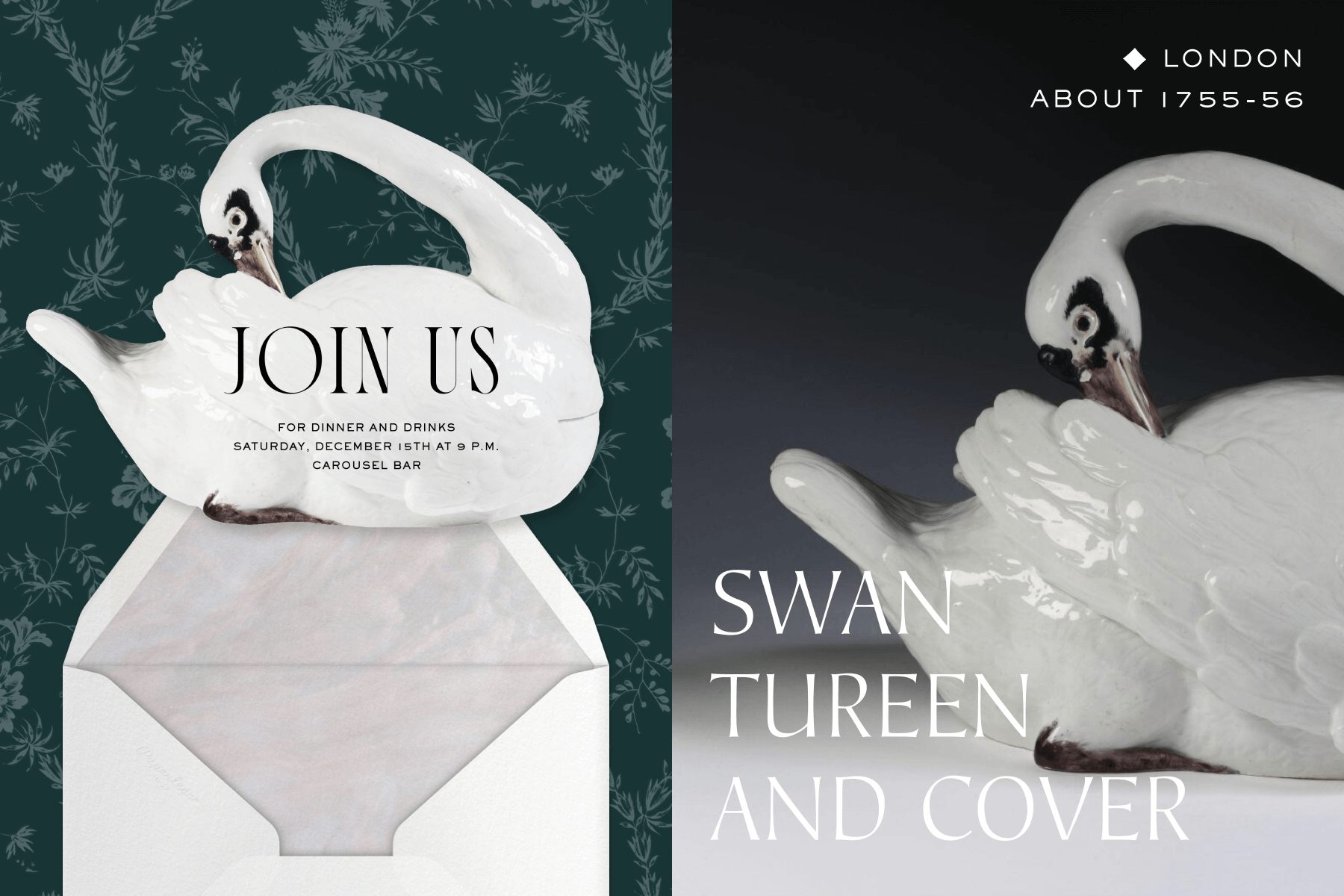

The object: Swan Tureen and Cover – London, about 1755-56

The history: Animal-shaped soup tureens, like this 17-inch-long swan by the Chelsea porcelain factory, were once de rigueur at formal dinners. “These whimsical, nature-inspired vessels were often playful visual statements, designed to surprise and amuse guests, and typically accompanied the first savory courses of grand banquets,” Calver explains. “This trend likely originated from the Meissen porcelain factory’s exploration of naturalistic designs in the mid-18th century, which quickly influenced English pottery and porcelain makers, as well as French potteries producing tin-glazed earthenware.”

The design notes: Says Di Chiara, “We loved the elegance and playfulness of the swan’s silhouette, and wanted to preserve it as-is to celebrate the original beauty. It was already the perfect vehicle for an invitation because it had open space for text.”

“Eye of the Pearl” by the V&A Museum for Paperless Post

The object: Eye miniature – England, early 19th century

The history: With a pearl frame and real diamond tears, this tiny painting—fashioned into a brooch appropriate for formal affairs—was likely given as a symbol of affection. “Eye miniatures came into fashion at the end of the 18th century and often served as intimate love tokens, imbued with deep personal significance,” Calver tells us. “The anonymity of many of these pieces, with unsigned works and the often-unknown identities of the individuals depicted adds to their mystery.”

The design notes: “This eye caught our eye!” says Erica Tagliarino, Paperless Post’s Senior Production Designer. “It really inspired me as a symbol of intimacy and devotion. The Lover’s Eye is an invitation for human connection, which is what entertaining is all about… and I love the idea of wearing a small part of your beloved’s likeness to a party.”

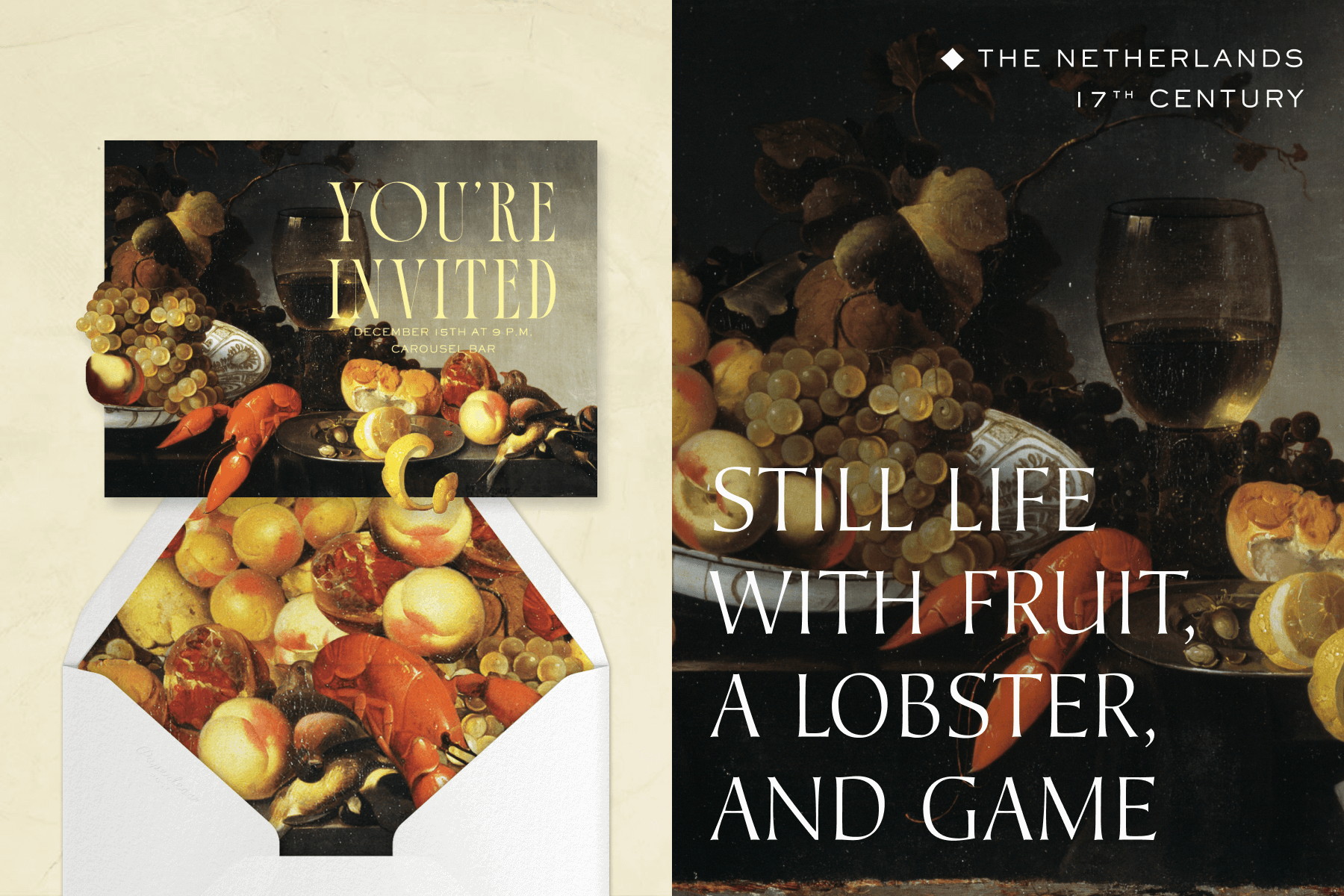

The object: Still Life with Fruit, a Lobster, and Game – The Netherlands, 17th century

The history: Ever squeeze a lemon into your wine? The pairing of citrus fruit and a glass of white wine in this rich oil painting by Michiel Simons, along with other Dutch still life paintings, suggests that it was customary to season wine with lemon in the 17th century. The lush scene, which also features a lobster, fruit, bread, and birds, “captures a moment of sensory indulgence and abundance,” according to Calver. “It reflects a narrative of luxury and consumption, embodying not just the opulence of the subjects [depicted], but also the underlying cultural values of 17th-century Dutch society.”

The design notes: One of the more obviously entertaining-related “objects,” Simons’s evocative still life appears practically unaltered in our collection—save for a lemon peel, fruits, and lobster claw breaking free from their rectangular confines. As Senior Art Director Mariya Pilipenko tells it, “Our goal with this collaboration was to showcase the abundance, history, and contemporary voice of the V&A. It was important for us to honor each object, interpreting the artwork into stationery while also keeping as many of the original elements as we could.”

The object: Chelsea Porcelain Plate – London, about 1755

The history: Ceramics from London’s Chelsea porcelain factory, which dominated the English porcelain market from the 1740s to the 1760s, were just as coveted by 18th-century high society as those imported from China and Japan. This Asiatic plate is a perfect example of why. “With its elegant blue and white bird motifs, this Chelsea dinnerware design beautifully captures the essence of Georgian style, reflecting the era’s refined tastes and appreciation of chinoiserie,” Calver explains. “The beautiful and delicate pattern conjures up images of multi-course feasts and grand celebrations, reflecting an era of indulgence and opulence. Today, the decorative design connects the past with the present, providing a stunning backdrop for contemporary dining experiences.”

The design notes: “We were drawn to the concept of an invitation on a dish, and this Chelsea porcelain soup plate, with its beautiful, natural landscape painted in a blue underglaze, was the perfect canvas,” Di Chiara tells us. “Our goal was to preserve the essence of the original design with minimal alteration—but this being an invitation, we needed to find space for event details, too. We decided to bring them together in a complementary envelope liner, offering a modern take on a timeless, decorative style.”

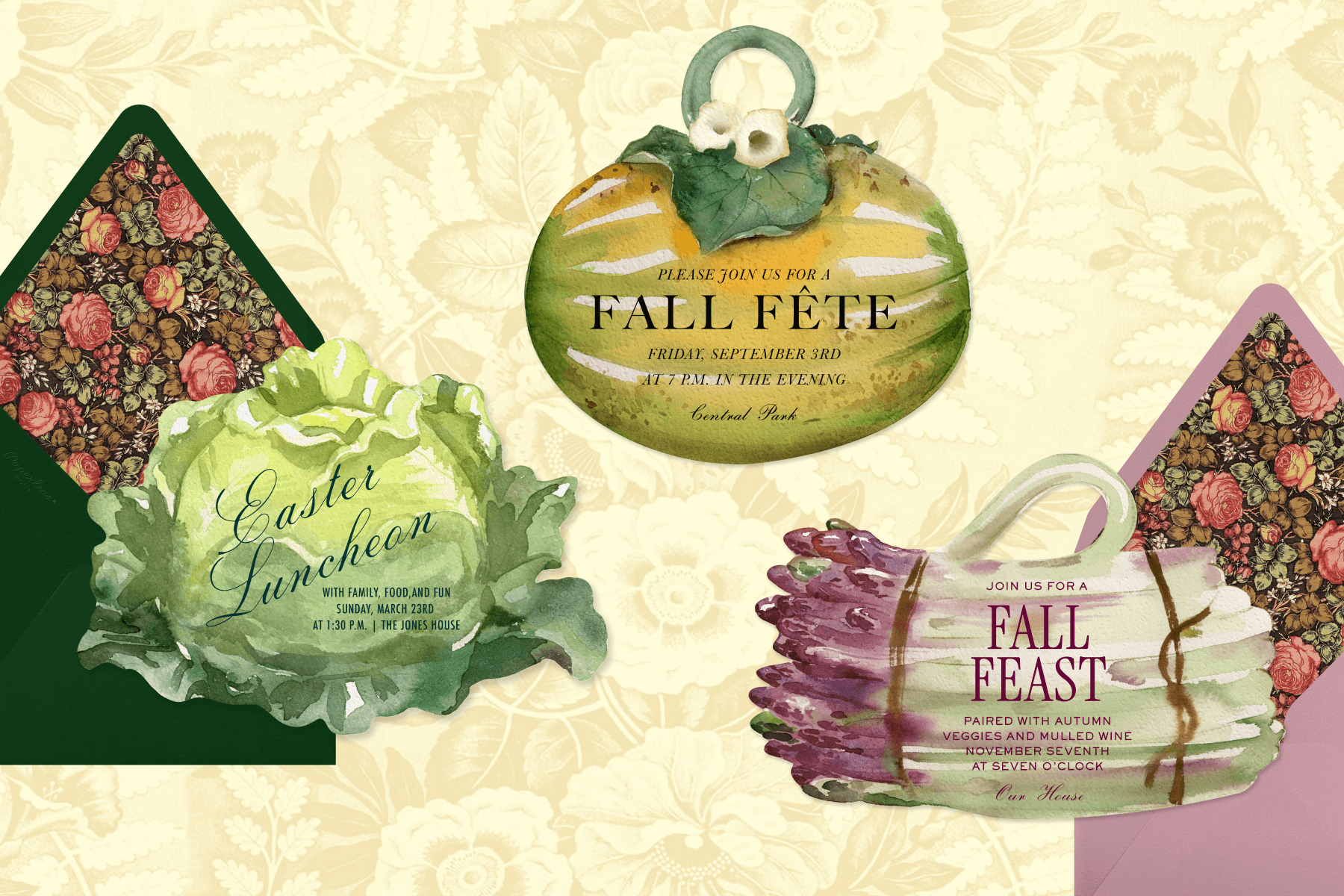

The objects:

Cabbage Tureen – Europe, about 1830-70

Asparagus Tureen – London, about 1756

Melon Dish – England, about 1756

The history: Dinner parties in the 1700s were often as much about the theatrics of entertaining as the food being served. Enter trompe l’oeil (‘fool the eye’ in French) serveware, which imitates things found in nature with its attention to detail and often a dash of humor—all the better to spark conversation among guests. Typically made of soft-paste porcelain, a delicate material well-suited for dessert, guests may have been momentarily tricked into thinking their final course was a savory bundle of asparagus or fresh head of cabbage—only to be amused (and relieved!) to find a sweet treat hidden inside.

The design notes: “We took a bit of an editorial approach to many of our subjects—some, we lovingly re-illustrated, making sure that every detail was captured,” explains Pilipenko, who used watercolor paint to painstakingly transform several pieces from the V&A’s extensive collection.

“Tea Pot” by the V&A Museum for Paperless Post

The object: Reed & Barton Teapot – Taunton, Massachusetts, 1892

The history: Most likely part of a larger tea set, this electroplated teapot—made of inexpensive industrial Britannia Metal with silver veneer—is inscribed with a dedication to a couple on their “silver” wedding. It was produced by Reed & Barton, a factory in Taunton, Massachusetts that produced not only electroplated serveware, but also weapons for the Union army during the Civil War, and later, Olympic medals. When this teapot was new, it would have looked like real silver, but cost a fraction of the price.

The design notes: “Teapots are a symbol of social gatherings, so this object fits perfectly with our theme of entertaining,” says Pilipenko. “We were captivated by its intricate details and unique silhouette, which we reinterpreted using pen and ink. The ornate greenery motif was then incorporated into the liner.

Additionally, we loved that this teapot was made with British metals and manufactured in the States—which feels not so dissimilar to the collaborative process that went into this very collection!”

Cheers to Amelia Calver and the V&A! Explore and send our new collection of invitations now.